Grup A Streptococcus (GAS) M1T1 klonu 1980’lerde nekrotizan fasiit ve toksik şok sendromu gibi invazif epidemik infeksiyonların başlıca nedeni olarak görülmeye başladı. M1T1 klonunun evrimleşmesinde taşınabilir genetik elemanların yatay transferi önemli bir rol oynadı. Bakteriyofajda kodlanmış belirteçler DNase Sda1 ve süperantijen SpeA2 sırasıyla virülans ve kolonizasyonun artmasına yardımcı oldu. 2011’de Hong Kong ve Çin’deki başlıca nedeni emm12 GAS olan kızıl salgınları, Queensland Üniversitesi’nden araştırmacıları, genom dizilemesi tekniklerini kullanarak, son 100 yıldır büyük ölçüde kökü kazınmış olan kızılın ikinci en sık görülen nedeni olan emm1 GAS’i ele almaya yöneltti. Hong Kong’tan 18 emm1 ve Çin’den 16 emm1 izolatının genomik analizi, M1T1 genomik arkaplanında emm12 kızıl klonlarının yayılımıyla ilişkili aktarılabilir genetik elemanların varlığını ortaya koydu. Bu aktarılabilir genetik elemanlar, SSA ve SpeC süperantijenlerinin eksprese edilmesini ve tetrasiklin, eritromisin ve klindamisin direncini sağlıyor. M1T1 klonunda aktarılabilir DNA’nın çok ilaca direnci ve yeni bir süperantijen repertuarının ekspresyonunu sağlayacak biçimde yatay transferinin gösterilmiş olması, bu genetik elemanların küresel ölçekte yayılımı hakkında kamuoyu bilincinin artmasını gerektiriyor.

Scarlet fever making a comeback

An international study led by University of Queensland (UQ) researchers has tracked the re-emergence of a childhood disease which had largely disappeared over the past 100 years.

An international study led by University of Queensland (UQ) researchers has tracked the re-emergence of a childhood disease which had largely disappeared over the past 100 years.

Researchers at UQ’s Australian Infectious Diseases Centre have used genome sequencing techniques to investigate a rise in the incidence of scarlet fever-causing bacteria and an increasing resistance to antibiotics.

UQ School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences researcher Professor Mark Walker said the disease had re-emerged in parts of Asia and the United Kingdom.

“We have not yet had an outbreak in Australia, but over the past five years there have been more than 5000 cases in Hong Kong (a 10-fold increase) and more than 100,000 cases in China.

“And an outbreak in the UK has resulted in 12,000 cases since last year,” he said.

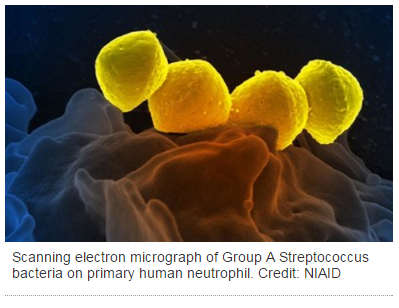

Scarlet fever, which mainly affects children under 10, is spread by Group A Streptococcus (strep throat bacteria) known as GAS.

Symptoms include a red rash on the skin, sore throat, fever, headache and nausea.

Serious illness can be treated with antibiotics.

UQ School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences researcher Dr Nouri Ben Zakour said the research results were “deeply concerning”.

“We now have a situation which may change the nature of the disease and make it resistant to broad-spectrum treatments normally prescribed for respiratory tract infections, such as in scarlet fever.

She said penicillin continued to provide an excellent treatment for patients who were not allergic to it.

Dr Ben Zakour said the rise in scarlet fever could pre-empt a future rise in rheumatic heart disease, which causes permanent heart damage.

“With this heightened awareness, we can now swiftly identify scarlet fever-associated bacteria and antibiotic resistance elements, and track the spread of scarlet fever-causing GAS strains,” she said.

Dr Ben Zakour said the evolutionary forces driving the outbreaks were unknown, but bacterial causes, the immune status of people contracting scarlet fever, and environmental factors such as temperature and rainfall could all play a significant role.

“Only a continued study of the patterns, causes and effects of health and diseases will determine the full impact these recent gene changes will have on the global GAS disease burden,” she said.

The research, published in Scientific Reports, was conducted by Associate Professor Scott Beatson’s microbial genomics group at UQ, with collaborators at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, UK, and in China at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, The University of Hong Kong, and the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology.

The work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Australian Research Council, and the Research Fund for the Control of Infectious Diseases Commissioned Grant of the Hong Kong Government.

Media: Dr Nouri Ben Zakour, n.benzakour@uq.edu.au, +61 7 3365 8549; Professor Mark Walker,mark.walker@uq.edu.au, +61 7 3346 1623; Associate Professor Scott Beatson, s.beatson@uq.edu.au.