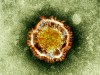

An electron microscope image of a coronavirus, provided by the British Health Protection Agency, is shown. The virus is part of a family of viruses that cause ailments, including the common cold and SARS, and was first identified last year in the Middle East. (Health Protection Agency)

An electron microscope image of a coronavirus, provided by the British Health Protection Agency, is shown. The virus is part of a family of viruses that cause ailments, including the common cold and SARS, and was first identified last year in the Middle East. (Health Protection Agency)

Published Monday, July 8, 2013 8:19AM EDT

TORONTO — This week experts from around the world will begin meeting to advise the World Health Organization on the new MERS coronavirus.

One of the key reasons the so-called emergency committee is being called together at this point, a senior WHO official says, is because so many questions remain unanswered about the virus that causes Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome.

“There’s a whole lot of information which we don’t understand,” Dr. Keiji Fukuda, assistant director general for health security and the environment, says of the WHO’s unexpected move, announced Friday.

Efforts to find the source of the MERS virus and to answer basic questions about the way it moves into and among people have been frustratingly slow to yield results.

A decade ago, when the SARS virus emerged, developments moved much more rapidly. Within two-and-a-half months of the new disease hitting the world’s radar, scientists in Hong Kong had found the SARS coronavirus in civet cats, which are eaten as a delicacy in the part of southern China where SARS emerged.

More than a year after the MERS virus was first isolated, the world still has no idea how this new coronavirus is finding its way into human lungs in several Middle Eastern countries, most notably Saudi Arabia.

But there is renewed hope that the work of a renowned U.S. research team may begin to pay dividends.

The scientists, from the Center for Infection and Immunity in the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University, hope to soon be able to begin testing animal samples imported from Saudi Arabia.

It’s believed the new MERS virus originated in bats but is probably infecting people via some animal or animals that serve as a bridge.

Getting the samples into the United States has been a lengthy endeavour, says centre director Dr. Ian Lipkin, who is famed at finding new viruses.

That’s because of U.S. rules designed to keep the country free of the foot and mouth disease virus, a highly contagious and economically devastating pathogen that infects hooved animals.

Saudi Arabia has foot and mouth disease, so technically, specimens that might contain the virus cannot be brought into the United States. Lipkin says it has taken months to devise a work-around, but one has been approved.

“And it’s gone all the way up, frankly, to the White House. Very complicated, very difficult. A major impediment to getting an answer,” he says.

All Saudi samples destined for Lipkin’s lab that are from ungulates — hooved mammals such as goats, camels, sheep — will be pre-tested for foot and mouth disease virus at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal Disease Center on Plum Island, off the tip of Long Island, N.Y.

If samples are found to be free of the virus, they will be released to Lipkin’s laboratory, where scientists will be able to begin studying them to look for MERS or MERS-like viruses, or for antibodies to the virus.

These specimens may arrive in the U.S. this week, Lipkin says. “And then we’ll get into gear doing the molecular and serological assays.”

Lipkin says he doesn’t know how many animal samples there will be in the shipment or how many types of animals have been sampled. The specimens were taken during his team’s second trip to Saudi Arabia, in April.

A previous shipment of bat samples that were collected during a trip his team made last October contained what he felt was a highly promising lead.

A small trace of virus taken from an insect-eating bat looked to be a match for the MERS virus. But the samples in the shipment arrived in poor condition — essentially ruined.

“So we had a lead. We tracked the lead. Unfortunately we don’t have enough material to be absolutely confident of the finding. That is what it is and I can’t pretend it’s anything else,” Lipkin says.

Asked if he feels any closer to finding the source of the virus, he admits to frustration.

“What I want to do is to go in with a large team and collect thousands of bats across the country and do this in a rigorous, concerted, thorough and definitive fashion. That’s what I really want to do,” Lipkin says.

“Right now I’m jumping here, I’m jumping there, I’m capturing what I can. And it’s not ideal.”

To do that, though, he needs resources. Much of the work to date has been unfunded. “Are people concerned about MERS? Or are they not concerned about MERS? There’s no big push at this point,” he notes.

In addition to the research aimed at identifying the virus’s reservoir, Lipkin’s team is trying to help answer another key MERS question: Are there mild or symptom-free cases that are evading detection?

Most diseases have a spectrum of illness, with severe cases making up the tip of the iceberg. So far with MERS, only the tip has been visible. More than half of known cases have died.

But there have been a few mild cases spotted, giving experts hope there may be more that aren’t being picked up by existing surveillance systems, which are set up to look for the virus in people who are critically ill.

One way to answer this question is by looking for antibodies in the blood of people who may have been exposed to the virus. Antibodies are proof of prior infection.

Lipkin’s laboratory has been testing blood samples from more than 200 individuals from Saudi Arabia. Some of the samples were taken from known cases, others from contacts of cases.

The team doesn’t know which is which, but they’ve studied the samples using a variety of assays and have reported the results to the Saudi deputy health minister, Dr. Ziad Memish. Memish has the code which outlines the source of each sample.

Comparing the lab’s results to Memish’s master list should start to give a clearer picture of whether the infection is more common than has been seen to date.

“I don’t know which samples are people who had active disease, which people recovered from disease, which people were contacts,” he says. “And until I have the code cracked, I can’t really be certain of what we’ve learned.”

Lipkin says results of this study will be submitted for publication in a journal.