Doctor Being Treated for Ebola in Omaha Dies

Doctor Being Treated for Ebola in Omaha Dies

![]()

By ABBY GOODNOUGH and TOMMY TRENCHARD I NOV. 17, 2014

WASHINGTON — This time, the challenge of Ebola was much steeper for the doctors and nurses at Nebraska Medical Center, one of a handful of hospitals specially designated to handle cases of the deadly virus in the United States.

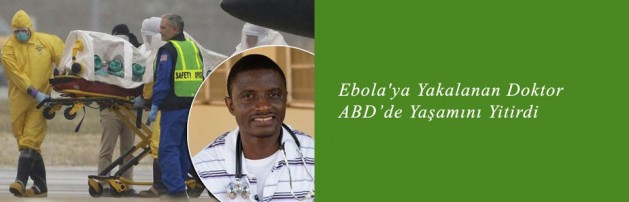

Unlike the two Ebola patients they had successfully treated earlier this year at the hospital’s biocontainment unit in Omaha, the man who arrived from Sierra Leone on Saturday, Dr. Martin Salia, was in extremely critical condition. Dr. Salia, a legal permanent resident of the United States who had been working as a surgeon in Sierra Leone, died early Monday morning, barely into his second day of treatment, but almost two weeks into his illness.

“Even the most modern techniques that we have at our disposal are not enough to help these patients once they reach a critical threshold,” said Dr. Jeffrey P. Gold, chancellor of the University of the Nebraska Medical Center, the hospital’s academic partner.

Dr. Philip Smith, the medical director of the biocontainment unit, said that Dr. Salia, 44, had initially been tested for Ebola in Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, on Nov. 7, but that the test came back negative. He was retested there on Nov. 10, at which point the results were positive. Dr. Smith said such false negatives were not uncommon early in the illness.

Doctor Describes How Ebola Patient Died

Dr. Daniel W. Johnson, the director of critical care at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, discussed how Dr. Martin Salia died after being brought to the hospital with advanced Ebola symptoms.

Video by Reuters on Publish Date I November 17, 2014. Photo by Eric Francis/Getty Images.

Dr. Daniel W. Johnson, a critical care specialist at Nebraska Medical Center, said that Dr. Salia’s kidneys had stopped functioning and that he was laboring to breathe when he arrived at the hospital late Saturday afternoon after a 15-hour flight. Doctors quickly tried two treatments they had used on their other Ebola patients: an experimental antiviral drug and a plasma transfusion from the blood of an Ebola survivor, which researchers believe may provide antibodies against the virus.

But Dr. Salia was already so ill that within hours of his arrival at the hospital, he needed continuous dialysis to replace his kidney function. By the pre-dawn hours of Sunday, he was in respiratory failure and needed a ventilator, Dr. Johnson said on Monday. Around the same time, he added, Dr. Salia’sblood pressure plummeted.

“He progressed to the point of cardiac arrest, and we weren’t able to get him through this,” Dr. Johnson said at a news conference in Omaha. “We really, really gave it everything we could.”

Dr. Smith said he did not know how Dr. Salia had contracted the virus. “He worked in an area where there was a lot of Ebola disease, much of it probably unrecognized,” Dr. Smith said, “and there were many opportunities for him to have contracted it.”

In the frenetic neighborhood of Kissy, on the eastern end of Freetown, an eerie quiet hung over the United Methodist Hospital on Monday as news spread that Dr. Salia had died. He was the chief medical officer and the only surgeon at United Methodist Kissy Hospital, according to United Methodist News Service.

Leonard Gbloh, the administrator of the hospital, said he did not think Dr. Salia could have contracted Ebola there.

The hospital even stopped all surgical work several months ago as a precaution, Mr. Gbloh said. Now, the hospital is being decontaminated and several staff members who came into contact with Dr. Salia after he fell ill are in quarantine there.

But Mr. Gbloh said that Dr. Salia — whose wife and two children live in New Carrollton, Md. — had also been working at other hospitals and clinics in the area.

He said that Dr. Salia would be remembered as kind and dedicated, adding, “He was a great professional, always willing to work overtime.”

Yahya Tunis, a spokesman at the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, said he had known Dr. Salia well. He recalled how, during a doctors’ strike earlier in the Ebola outbreak, Dr. Salia had turned up at Connaught Hospital in Freetown and persuaded his colleagues to return to work.

“He had left the comforts of America to come and work here in his home country,” Mr. Tunis said. “We are very saddened by his passing.”

Despite signs that Ebola is in decline in eastern parts of Sierra Leone, as well as in neighboring Liberia, the virus is still rampant in Freetown and its environs. According the government’s count, the country saw more than 500 new cases last week, with the highest number in Freetown.

Five other doctors in Sierra Leone have contracted Ebola; all have died. Although the State Department arranged for Dr. Salia’s travel to Omaha from Sierra Leone on a specially equipped plane, patients or their sponsoring organizations are typically responsible for the costs of such evacuations.

Dr. Salia is the second patient to die of Ebola in the United States. The first,Thomas Eric Duncan, died in early October at a Dallas hospital after traveling there from Liberia. Two nurses who cared for Mr. Duncan, Nina Pham and Amber Joy Vinson, also contracted the virus but recovered.

Two other Americans who contracted Ebola in West Africa, Dr. Rick Sacra, a missionary doctor, and Ashoka Mukpo, a freelance cameraman, recovered after being treated at the Nebraska unit in September and October. But both arrived there earlier in their illness and did not need dialysis or a ventilator. Each patient at the Nebraska unit has received a different experimental drug, and doctors say it is hard to know whether they helped Dr. Sacra and Mr. Mukpo.

Dr. Salia’s body will be cremated, Dr. Smith said, adding that he and his staff are still waiting for the results of Dr. Salia’s blood tests, which will show how much virus he had in his body.

Dr. Smith said the nurses, doctors and respiratory therapists who had cared for Dr. Salia would monitor their temperatures and be on alert for any symptoms of the virus in the coming weeks, logging the results into an electronic database that will be checked daily. But they will continue to work, he said.

“The staff gave it everything and then some,” said Rosanna Morris, the hospital’s chief nursing officer. “Now they need a little time to grieve and really find peace within themselves, awaiting our next patient.”

Abby Goodnough reported from Washington, and Tommy Trenchard from Freeport, Sierra Leone.