Ebola outbreak stirs anger in fragile Liberia

BY JAMES HARDING GIAHYUE AND BATE FELIX

MONROVIA/DAKAR Sat Sep 6, 2014 5:04am EDT

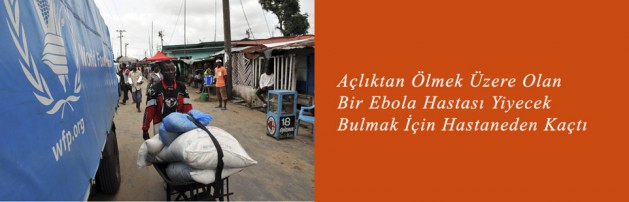

A resident of West Point neighborhood, which has been quarantined following an outbreak of Ebola, pushes a wheelbarrow full of food rations from the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) in Monrovia August 28, 2014.

A resident of West Point neighborhood, which has been quarantined following an outbreak of Ebola, pushes a wheelbarrow full of food rations from the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) in Monrovia August 28, 2014.

(Reuters) – When a starving Ebola patient escaped from a treatment center in Monrovia and staggered through a crowded market in search of food, bystanders who scattered in his path voiced their anger not at him but at Liberia’s president.

To many in this impoverished West African country, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s government has not done enough to protect them from the deadly virus. Ebola has killed more than 1,000 people in Liberia since its arrival six months ago. Across West Africa, the death toll from the world’s worst Ebola outbreak has surpassed 1,900.

Panicked residents said the patient was the fifth to escape in recent weeks from the understaffed ELWA hospital. Dozens watched anxiously as workers in protective clothes bundled the struggling patient into a truck and drove him back.

“The patients are hungry, they are starving. No food, no water,” said one terrified woman in the crowd. “The government need to do more. Let Ellen Johnson Sirleaf do more!”

A Noble Peace Prize winner for her work on women’s rights, Johnson Sirleaf had made gradual progress before the epidemic in rebuilding Liberia after a 1989-2003 civil war.

She now seems destined, however, to spend the last two years of her presidency dealing with the fallout from Ebola.

Feted internationally since she became Africa’s first female head of state nine years ago, Johnson Sirleaf’s reputation at home has been dogged by a slow improvement in living standards. Some critics saying she is out of touch with poor Liberians.

The 75-year-old former World Bank official now faces mounting anger over her handling of Ebola. Her government has been denounced for causing food shortages by imposing quarantine on affected communities, while healthcare workers have walked out on strike after several of their colleagues died.

The president has also faced criticism for sending troops to quell protests in the ocean-front West Point slum of Monrovia. A 15-year-old boy was fatally shot after soldiers opened fire on a crowd trying to break out of a quarantine there.

Opponents have called for Johnson Sirleaf to resign, but her government has said it is doing everything possible, given the scant resources at its disposal.

“Care and attention should be given to helping people who need it the most and we can get into the politics later,” Information Minister Lewis Brown told Reuters. “We’re in a better position than we were several weeks ago in this fight.”

Johnson Sirleaf has taken bold steps. Declaring a state of national emergency last month, she closed schools to prevent them becoming breeding grounds for infection, and sent home all non-essential government staff.

But the disease is far outpacing efforts to control it. Medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) said this week a further 800 Ebola beds were needed in Monrovia alone, and it called for foreign military teams to be deployed.

“Localized unrest and public criticism of government failures look set to increase as the health situation worsens and the authorities fail to find adequate responses,” warned Roddy Barclay of consultancy Control Risks.

NO CLEAR STRATEGY

Tom Frieden, head of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), warned this week after a visit to the region that the outbreak was gathering pace and threatened the stability of fragile West African nations.

Although the epidemic was detected deep in the forests of neighboring Guinea in March, Liberia now accounts for more than half the 1,900 people who have died from the virus, which has also struck Sierra Leone, Senegal and Nigeria.

“The government was not clear on how to engage the outbreak,” said Francis Colee, an environmentalist living in Monrovia, who said Liberia had reacted poorly compared with its neighbors. “The government’s response mechanism has been very disappointing.”

Liberia is not the only government to face criticism as health systems have buckled. In Sierra Leone, struggling to recover from its own 1991-2001 civil war, frustration has mounted at the government’s handling of the crisis. After strikes by healthcare workers, President Ernest Bai Koroma dismissed his health minister last month.

Johnson Sirleaf similarly sought to quell criticism by dismissing senior officials who failed to report for work.

For Barclay of Control Risk, recognition that the opposition cannot offer better alternatives due to Liberia’s weak institutions, meant popular anger was unlikely to bubble over.

“Despite causing significant turbulence, such trends are unlikely to destabilize government or fundamentally alter the balance of power,” he said.

A major challenge has been informing a poorly educated population about a disease which had never before struck in West Africa. Burial traditions of washing the dead by hand have fueled the spread of the highly contagious disease but with many citizens unable to read, education campaigns have been slow to reach their mark.

“People are still not aware of how the virus can spread,” Emmanuel Geayon, a university student. “The Ebola messages and awareness campaign are not in the vernacular.”

Campaigns have also been dogged by deeply engrained mistrust of the political elite. Rumors had circulated early in the outbreak that Ebola was a myth and politicians were poisoning wells in Monrovia to win access to more aid money.

On the muddy streets of rain-soaked Monrovia, billboards now proclaim “Ebola is Real”. On the radio, songs describe the symptoms of the disease and how to avoid infection.

The World Health Organization has warned that up to 20,000 people may be affected before the outbreak ends. It has laid out a $490 million roadmap for tackling the outbreak but support from foreign donors has been slow to arrive.

“In a way, we feel saddened by the response,” Johnson Sirleaf told CNN in an interview.

The president has admitted that Liberia – which had only 50 doctors for its 4.5 million people on the eve of the outbreak – does not have the resources to cope.

Even in hospitals in Monrovia, a scarcity of gloves and protective clothing has put doctors at risk when treating patients – and in rural clinics resources are even scarcer. Several top emergency doctors have died in their duties.

Johnson Sirleaf apologized last month for the high death toll among healthcare workers, and pledged more money for ambulances and new treatment centers.

But the suspension of flights by international airlines and the closure of borders by neighboring states has complicated efforts to respond.

“How do we get in the kinds of supplies that we need? How do we get experts to come to our country? Is that African solidarity?” Information Minister Brown asked.

(Additional Reporting by Emma Farge; Writing by Bate Felix and Daniel Flynn; editing byJanet McBride)